Comic Book Writer AMY CHU's unconventional career

Amy Chu writes comics like Deadpool, Poison Ivy, and Red Sonja, but that hasn't always been her job. She's also started a magazine for the Asian-American community, consulted for non-profits, biotechnology companies, and pharmaceutical companies, and run the Macau tourism bureau in Hong Kong. Amy talked to us about following an unconventional career path, drawing on her past experiences as a comic book writer, and how she knows she's found her passion.

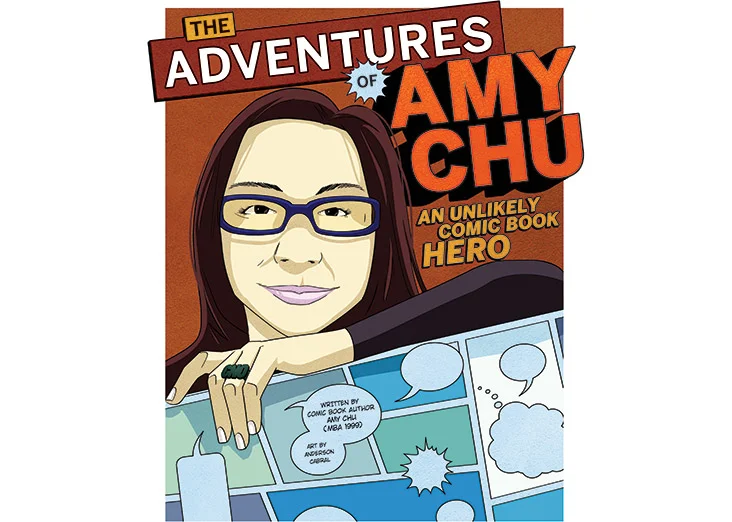

Amy's avatar

FAST FACTS ABOUT Amy

Where she’s from: Iowa

Education: Dual bachelor’s degrees from Wellesley College and MIT and an MBA from Harvard Business School

Where she lives now: Princeton, New Jersey

Growing up she wanted to be: a physicist

Now she’s: a comic book writer

Tell us about yourself growing up!

I was a straight-up nerd. I grew up all over, but I spent my formative years in Iowa.I didn’t read comics. I’m sure I read Wonder Woman, I’m sure I did all that stuff, but it wasn’t in a way that most comic book nerds are, like, “I remember my first issue was issue XYZ of X-Men.” I was pretty nerdy. I was reading, Rise and Fall of the Third Reich kind of stuff when I was 12. I was on the chess team. I was on the math team.

What was it like doing a dual degree at Wellesley and MIT?

It was a five-year program. If you get into both schools, you can get both degrees. You start off two years at Wellesley, and then you’re basically at MIT full-time. I started off going back and forth, from the beginning. I think my year there were maybe three women who did it, because it is really hard.

Can you talk about the job you had throughout college?

One of my first jobs at Wellesley, basically what funded me through Wellesley was, I did night graphic design at Monitor Group. That was my first introduction to management consulting. I was doing all their Five Forces, Michael Porter presentations, making all their stuff look really nice, and they paid really well. I was working 20 hours or more doing these presentations.

I ended up working there many years. At a certain point, I switched to a lower-paying job as a research assistant. I knew that this was actually pretty good in terms of learning about how to research industries, competitors, that kind of thing.

Did you know what you wanted to do after college?

I like doing new things and start-ups, and I started a magazine, A Magazine, while I was at Wellesley and MIT. I took off six months to start this magazine with some friends in New York. It was an Asian-American magazine, and I was the first publisher. When I was at Wellesley, I was part of the group that got the first Asian-American Studies class on campus. I thought, “We need to increase awareness of what it means to be Asian-American at Wellesley.” I proposed that we do a literary journal talking about Asian-American experiences, so I launched that. That led into this magazine, because then I became friends with people at Harvard who were doing the same thing. We said, “We should do an Asian-American magazine for everybody.”

There was not a whole lot of understanding about people like myself. I was born in Boston. My experience is very different from somebody who just came from China.

How did you go from your magazine to non-profit consulting?

We weren’t profitable, and that’s when I ended up doing consulting again. I was writing proposals and business plans for non-profits to try to get them to operate more professionally. It’s helping people, using strengths that I have, crafting ideas. It involves strategic thinking. Then I got an offer from the United Way to run their management consulting program. That was kind of cool, because I had a budget, I could hire consultants, I could work with, like, the entire New York City social service agencies.

How did you end up working in Hong Kong?

I really liked what I was doing, but there’s not a lot of mobility in the nonprofit sector. You see people stay in the same position for 20 years, and I said, “I need to do something else.” I had met a woman from Hong Kong at a nonprofit fundraiser, and she was like, “Come to Hong Kong, if you’re looking for a new job. I’ll get you a job.” I did that, and she got me a job.

From ’95 to ’97, I was there as a Chinese-American expat. She introduced me to this woman named Pansy Ho, who is now the richest woman in Asia. She’s the daughter of Stanley Ho, who basically owns the gambling franchise in Macau. Back then, she was running a PR agency. She’s possibly one of the smartest people I’ve ever met. I started working for her. Her attitude was, if you’re smart, you’re on board. She started getting more involved in her dad’s business, and brought me along with her. I ran the Macau tourism office in Hong Kong. It was a very different expat experience, because everything I was doing was very local. I think that’s partly how I got into Harvard Business School.

I think I was always trying to fit myself into something that didn’t necessarily fit for me.

Why did you decide to go to business school?

At Monitor [where Amy worked during college], you do two, three years as an analyst, and you go to business school, so I had it in my head that I really needed to go to business school. It seemed like a good thing to do. I got the letter in Hong Kong. I vaguely thought maybe, well, I can do consulting properly. I thought I should try to be more conventional. There’s something to be said for having a really good consulting job, but I think I was always trying to fit myself into something that didn’t necessarily fit for me.

You did work for a consulting firm for a few years, then you switched gears again. What did you do next?

My Hong Kong employer, Pansy, had made a bunch of biotech investments in the US. In 2001, everything was going south, and she gave me a call, and said, “I need some help.” I did biotech start-up turnaround. Usually, the tech and the science are not the issue. It’s usually the management team and the strategy.

I got married and I had kids. All of a sudden, I had different needs in terms of my schedule. I ended up working for a series of biotech pharma companies in [the Princeton, New Jersey] area. Because I spent time at MIT, I get along pretty well within scientists, and the CTOs. I got pretty good word of mouth, so I ended up getting a fairly steady stream of business.

Sometimes my motivation is, “Well, there’s no reason I shouldn’t be doing this, other than it wasn’t in the game-plan.”

How did you get into comic book writing?

The comics thing was entirely by accident. My friend Georgia, who’s also a Harvard Business School alum, always knew she wanted to be a writer. She had written and directed a really great film. I was a huge fan of it, so we became really good friends. She wanted to start the comics company. I said, “I know how to do the infrastructure. I know how to set up a company. I’ll be the publisher; you write the comics.”

We wanted to write comics for young women, because we felt that was really under-represented. I said, “I’ll take this online class so I can understand how the sausage is made.” I’m in the class, and it’s all guys who all know about every single minutia about Thor and whoever, and I didn’t know any, at this point. But when it came down to it, you have to write a story, and I wrote the story, and people were like, “Wow, that’s actually really good.”

I got this feeling that I’m not really supposed to be here, which always makes me kind of angry. I said, “Oh, well, you don’t think that I could be a comic book writer? I’m going to be a comic book writer, and I’m going to write all these characters, because you seem to think that I can’t write Deadpool. Are you saying that I should be writing Squirrel Girl instead of Deadpool?” I decided, “Okay, well, I’m going to write Deadpool.” I wrote Deadpool last year.

Sometimes my motivation is, “Well, there’s no reason I shouldn’t be doing this, other than it wasn’t in the game-plan.”

You’ve written Poison Ivy and KISS comics. How do you get those jobs?

You have a pitch. You have to come up with an idea. KISS has been in comics for 40 years. “What can I add to that?” Well, KISS has not been done in a sci-fi setting, in the future, so I’m going to pitch KISS sci-fi. And they’re like, “Awesome, let’s do it.”

I wrote Poison Ivy, because she didn’t even have a series before, and she’s from 1966. Even to have six issues, the comics journalists were like, “We don’t know if she can carry her own series.” I’m like, “Really? We have, like, 15 versions of Robin, and he can carry his own series. You don’t think Poison Ivy can carry her own series?” She’s a scientist, and even if you strip away half of her abilities, she’s way more powerful than most characters in the universes.

I’m a fairly new writer, so I’m trying to be fairly broad in what I do, just because I’m very nervous about being typecast, as a woman, as an Asian, as a new person in this business. I’m trying to show range.

I’m like a screenwriter. I have to come up with a plot every 30 days. Who knew I could do that?

How does a comic book get produced?

For American superhero books, every 30 days, a new issue has to come out. It’s serialized fiction. The way it works is there’s a writer like myself doing the script. The script goes to the penciler. This is the person who literally is drawing 15 hours a day to hopefully not be late, because they’ll be fired. That page will go to an inker. The inker is the one that puts in all the line work, the depth and everything. It goes to a colorist, then it goes to a letterer, and then ideally it’ll come back to me, because I have to make sure the words are now fitting. Then it goes to the printer. That happens every 30 days.

I’m like, “I got Red Sonja five and six. Red Sonja five’s already overdue.” I’m like a screenwriter. I have to come up with a plot every 30 days. Who knew I could do that?

I just found out they want to do another arc of Red Sonja. I’m like, “I have to come up with a whole new story, Red Sonja seven, already?” The editors want somebody who can be on time and show up and come up with ideas, and that’s me and Red Sonja.

How is comic book writing different than other kinds of story telling?

It’s almost more like music composition, or it’s math, because every issue is 20 pages. You are trying to fit a narrative within 20 pages that’s engaging, so what it is really apportioning real estate. This is the architectural design part, because you’re walking someone through 20 pages of story, and for every good superhero story, there has to be action.

If you have an action scene, it requires at least five pages. If you want two action scenes, that’s half your book gone already. You want character development and developing the storyline of the piece. You basically have taken all your space. It’s like doing the New York Times crossroad puzzle. You’re just trying to come up with the right elegant solution that creates the whole story, right?

What keeps you interested and engaged with comic book writing?

It’s a challenge. It’s really hard for me. I love it. Some people are, I think, kind of dismissive of comics, and I can totally understand that, having come from outside, because I had no idea about all this, the complexities of it. It’s something that I’m still learning a lot about, and part of it is just, I want to get good at it. My first published story was 2014. In 2016 I wrote six issues. That was Poison Ivy. Now I’m on three titles.

I’m passionate about it because I see it as being really effective for storytelling, especially doing educational stuff. I would like to pursue more of that, doing more educational stuff, because I think there’s a lot of value to that, and just for me personally getting good at it, because it is kind of hard. It’s like writing haiku.

Amy attends a lot of conventions to show her work and network with editors, publishers, artists, and the comic book community.. Here she's having a little fun at the entrance to Dr. Who's TARDIS.

What fills your time outside of work?

It’s all work, pretty much. I have to take my kids to soccer, so I’m working at soccer practice. I would really, really like to be playing some more video games. We just got the Switch. I just can’t get around to it, because I’ve got two scripts waiting. For years and years and years, I’ve really loved shopping, I like going to the mall and buying makeup and stuff. In the last two years, all of a sudden, I don’t care about shopping anymore.

I must have found my passion, because I’m like, “I don’t have time to do the shoes.” I’m trying to work out this arc, because Poison Ivy is in New York City, and what’s she going to do to get out of New York City. This is my life now.

Do you consider issues of representation when you’re writing?

All the time. I have that opportunity in terms of how I represent women. Mainstream comics has been a certain way for a long time. Comics has also been very much activist in a lot of ways, but the representation of the people who write and draw hasn’t always been there. I can do it, so why not? I have the opportunity to take the established character and make her really a great character, so that’s what I’m trying to do.

Representation is important. I published my first comic in 2012, and I started going to conventions, and I would be the only woman on some panels. I started a comic book women group, just as support, and between that time and now we have 350 women in this group.

I think things have turned around, and Marvel in particular has done a good job of trying to be more female, because they’re seeing who’s buying comics. In order to get growth, you need to reach out, and if you’re not reaching out to women, you’re missing out on a huge market segment. They’re hiring more people. There are more women artists, more women writers. I’m definitely not the only one.

It is hard to do a good comic, but it’s not hard to start doing something.

What advice would you give someone who’s interested in comic book writing?

They should start making their own comic books. Self-publishing is so much easier. It is hard to do a good comic, but it’s not hard to start doing something. You actually have something that’s printed up that you can hand to editors, that you can show other artists, established artists, like, “I made a comic and it’s readable.” Editors need to see that you actually produced something, and that you have enough adult life skills to put something together, so that’s really how you break in. And you could potentially do even better doing that than trying to go the mainstream route and trying to get hired. You can be quite successful on your own, doing your own stories, selling, crowd-funding them, et cetera.

And you will also know whether this is something you want to do after you do it. People think they want to do something, but when you actually have to do it, it’s a whole other thing.

How does your life now compare to what teenage you thought being an adult would be like?

I think teenage me thought I was going to be a physicist for some reason, and I was terrible at physics. I certainly never thought I was going to be a comic book writer. I’m sure teenage me would probably think this is kind of rad actually, that this is how I turned out.

I have a 13-year-old, and I think he’s like, before he was kind of like, “Yeah, whatever, my mom’s a comic book writer.” I think now he’s realized that not all moms are comic book writers, and it is kind of rad, because I write DC and I write Marvel stories, and his peers are kind of like, “Oh, that is cool.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.